The Culture of Japanese Ramen

A bowl shaped by everyday life, memory, and place.

1. Origins: From Across the Sea to the Streets of Japan

Ramen entered Japan in the late nineteenth century through port cities where Chinese cooks served warm, fast, and inexpensive noodle soups to laborers and merchants.

After the Second World War, wheat imports increased large-scale noodle production, and ramen stalls became part of the night landscape. A necessity became emotional comfort.

2. The Structure of Flavor: Broth and Noodles

A bowl of ramen rests on broth and wheat.

Broth: Layers of Umami

| Broth Type | Ingredients | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Animal-based | Pork bones, chicken bones | Richness, body, lingering finish |

| Seafood-based | Bonito flakes, dried sardines, kelp | Aroma, clarity, clean aftertaste |

| Vegetable-based | Onion, garlic, ginger | Soft sweetness, rounded edges |

Noodles: A Taste of Place

- Thicker noodles for hearty northern broths.

- Thin, quick noodles in fast-paced cities.

- Hand-kneaded noodles that retain wheat aroma.

3. Regional Ramen and the Stories They Carry

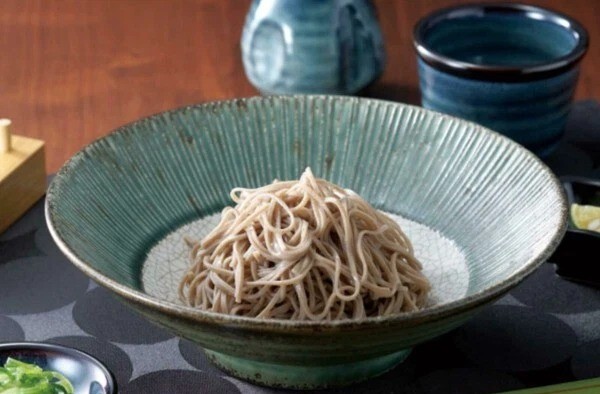

4. The Vessel: The Quiet Shape of Experience

Ramen does not end with the recipe. The bowl frames the experience.

- A wide mouth lifts aroma.

- A deep body holds heat.

- Glaze color shifts how we perceive broth.

- The weight of clay changes the pace of eating.

Ceramic vessels do not simply contain ramen—they complete it.

5. The Role of the Bowl: How Vessels Shape Experience

The bowl is not merely a container—it is a quiet protagonist.

Conclusion

Ramen is shaped not by luxury but by life itself. To eat ramen is to step into a small moment of care—heat settling into everyday rhythm.